At the BRICS summit, which opened in Johannesburg, a project for a common currency would allow member countries – China, Russia, India, Brazil, and South Africa – to trade with each other without relying on the US dollar. It would also enable them to avoid potential monetary sanctions from Washington. Is this a realistic ambition or just a communication stunt? Let’s analyze.

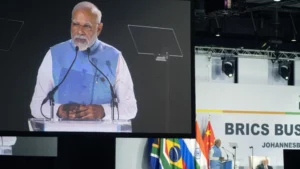

The common point between China, Brazil, India, Russia, and South Africa is their desire to combat US hegemony. And perhaps one day, a common currency. This is on the agenda of the BRICS summit (the name of the alliance formed by these five states) that opened on August 22 in Johannesburg. A common currency would allow them to escape potential American sanctions and demonstrate unity within this diverse group. But is this project realistic? We examines the issue with experts.

The goal for these five powers is to establish a monetary club in the face of the American giant, which has been dominant in the global monetary system since the end of World War II and the Bretton Woods agreements. In June, during the Summit for a New Financial Pact in Paris, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva publicly criticized American hegemony over trade agreements and proposed the creation of a currency for the BRICS group, similar to the euro.

“When you want to exchange rubles for Brazilian reals, you have to go through the dollar, through American banks. Detaching from the dollar is a crucial issue for peripheral countries in the international monetary system,” explains Alexandre Kateb, economist and president of the prospective firm The

Multipolarity Report.

The idea of a common currency appears even more ambitious considering the considerable economic weight of this group. The BRICS represent a quarter of the world’s GDP and 42% of the global population. Trade between China and Russia has skyrocketed, and Beijing is also Brazil’s largest customer for exports.

However, a common currency does not mean a single currency. The project does not aim to replicate the euro. “A common currency is added to national currencies and facilitates the settlement of trade imbalances between the countries that use it,” says Julien Vercueil, economist and lecturer at Inalco, where he is responsible for a seminar on the BRICS.

“This currency will not be used by individuals, but it will be used for transactions to facilitate trade between these countries, which until now relied on bilateral systems,” adds Alexandre Kateb.

While the principle seems well-defined, the details of the project remain unclear. “Several options are possible,” says Julien Vercueil, “ranging from a simple unit of account (with no other purpose than to serve as a common basis for accounting for mutual exchanges) to the pivot of a common system for securing settlements as an alternative to the Western Swift system, or even the beginnings of a true common currency, which would require the members to agree on the weights to be assigned to each of their currencies within a common basket.”

Agathe Demarais, a specialist in geopolitics and author of the book “Backfire” on the effects of economic sanctions, is skeptical about what she sees as a symbolic move. “For now, we are only at the stage of grand political statements. In my opinion, a BRICS currency makes no sense. If you want a unified monetary economy, you need roughly similar fiscal and economic situations, but the BRICS are completely different. It seems frankly unrealistic to me.”

The differences between the BRICS, both political and economic, are immense. It is difficult to imagine a harmonious architecture between China and Russia, authoritarian governments, and Brazil, India, and South Africa, with democratic cultures and more peaceful commercial relations with the West.

China in the driver’s seat

Moreover, among the BRICS, China, due to its status as a global heavyweight, would likely have control over the common currency, even though its monetary system remains tightly controlled. “China has bilateral surpluses with each of its BRICS partners, except Russia at the moment,” explains Julien Vercueil. “So, it is not only in an asymmetrical position in terms of its size and technological capacity but also in a destabilizing dynamic for the others. Therefore, it would bear the majority of the adjustment and coordination costs of the common currency. What would happen in the event of a debt crisis in one of the member countries? Who would act as the lender of last resort, and under what conditions in such a scenario? We don’t have an answer to this question.”

There are many unanswered questions when it comes to practical implementation. For a common currency to work, enthusiastic consent from the main commercial actors, i.e., businesses, is necessary.

Would they be willing to give up the dollar?

“There is a gap between the political will of governments and that of businesses,” notes Agathe Demarais. “In India or Brazil, businesses are free to do as they please. It is very complicated to ask them to change their processes, to fill out a new form at the bank… Logistically, it cannot be implemented in the short term.”

The issue of American sanctions

While the practical application of such an ambition remains to be established, the motivation of the BRICS is well-defined and can be analyzed in an increasingly tense geopolitical context. Faced with American sanctions, emerging countries have become aware of their vulnerability.

According to Alexandre Kateb, the red line was crossed with the war in Ukraine and the unprecedented financial sanctions imposed on Russia. “The freezing of the assets of the Russian central bank was a turning point: it was the first time a country was deprived of its monetary sovereignty. The United States and the G7 took a new step.”

Even before the invasion of Ukraine, the West had repeatedly demonstrated its ability to impede its adversaries economically. Agathe Demarais believes that the first key moment was in 2012 when Iran was excluded from the Swift system, which facilitates bank transfers. “Then, in 2014, there were the first sanctions against Russia, a major economic partner. And finally, in 2018, you had the beginning of the trade war between the United States and China, and measures aimed at restricting semiconductor exports.” In this changing context, where the dollar can be used as an economic weapon in the service of Western interests, emerging countries are looking for an exit strategy.

A “monetary multipolarity”

So, is the end of dollar hegemony near? Not so fast. “If we look at the statistics, we do see a progression of the yuan since February 2022 and the invasion of Ukraine, as Russia conducts trade in yuan. But today, we do not see an explosion of currencies other than the dollar or the euro. There is no plumbing available in the international financial system to bypass the United States,” reminds Agathe Demarais.

Julien Vercueil agrees: “The fact that Asian countries are growing faster than the United States necessarily means that they have the possibility to trade less in dollars. But we observe that there is still a very strong global demand for dollars, largely independent of the BRICS. The entire international monetary system has been structured around the dollar as the dominant currency, and no one, not even China, which still has intense trade with the United States, has an interest in its collapse